Superstitions, Patterns, and Control - Grade 8

This study consists of two modules, each focused on a single informational text that explores the reasons people have superstitions and rituals. Together these two short studies provide an introduction to the topic of superstitions, patterns, and control, and an orientation to the close reading of informational text. Through them, students are introduced to important ways of working with informational texts as well as to cycles of teaching and learning that feature significant amounts of reading, writing, and discussion.

Table of Contents

Writing Tasks

Title: “In a Field of Reason . . .:”: Unfamiliar Terms and Confusing Moments

Teacher Manual Instructions:

Session 1-A

Next, tell students they will have a chance now to identify unfamiliar terms and moments that are difficult, confusing, or unclear.

Take a few minutes to introduce students to the four-column chart shown on the next page and ask them to use it as a template for their own list of unfamiliar terms or confusing moments. They should title the chart “‘In a Field of Reason . . .’: Unfamiliar Terms and Confusing Moments.” Although students will be working together in their pairs or trios, each student should create and complete this four-column chart in her or his notebook.

Tell students that during this session’s work period they will be entering information in the first two columns only. They will add information to columns three and four later.

- The first column will indicate the line number in the text where the difficult, confusing, or unclear moment is located.

- The second column will consist of the unfamiliar terms and confusing moments students marked.

Give the groups 4-5 minutes to work on the first two columns of their chart. Use this time to circulate around the room and confer with groups about what they recorded.

Title: Lawyer Notes

Teacher Manual Instructions:

Session 2-D

Tell students that before they write this paper, they will spend the first part of the work period fleshing out as many ideas as possible.

Begin by asking students to recap what they know about the following ideas. Students should provide evidence from the texts to support their responses. Encourage students to use the charts and their writings in their notebooks as support.

Why people have superstitions. (Students should go beyond stating that people believe their superstitions will bring them good or bad luck. Support them to talk about such things as “pattern recognition” and the “illusion of control,” which were in both unit texts.)

The differences between a superstition and a ritual.

What one needs to know to determine whether a superstition is helpful

or harmful.

Place students in pairs and ask them to take about 15 minutes to skim through both texts with their partners to gather notes on several lawyers. Even though students are only required to write about two lawyers, encourage them to gather information on more than two so they will have a choice of lawyers to write about.

Next, give the pairs about 2-3 minutes to team up with another pair to share their notes.

Title: Argument: Writing Across Texts Explaining the Behavior of Lawyers

Teacher Manual Instructions:

Session 2-D

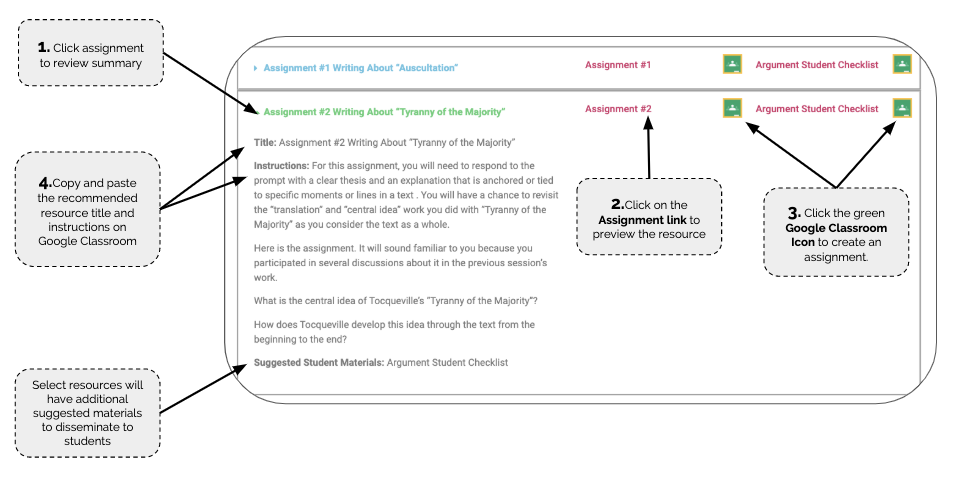

Suggested Student Materials: Argument Student Checklist

Charts for Discussion

Title: What We Learned About Superstitions and Rituals

Teacher Manual Instructions:

Session 1-A

After you’ve finished reading the text aloud, tell students that they will have an opportunity to discuss what they learned about superstitions and rituals from the first reading of this text. Place students in pairs or trios and give them 5-6 minutes to work together to create a list in their notebook on what they learned about superstitions and rituals from this text. The groups should consider the big ideas in the text, making sure that they can provide evidence from the text as support. They should title this first list “What We Learned About Superstitions and Rituals.”

Facilitate a short, whole-group share where the class collaborates to create a master list of this same type of information. To create this master list, invite students to share what they learned about superstitions and rituals from reading this text. Students should point to places in the text to support their responses. Encourage students to share the big ideas from the text, using the examples of particular lawyers as support for those ideas. Capture student

Title: Why Do Lawyers Engage in Rituals During Trials?

Teacher Manual Instructions:

Session 1-C

- Facilitate a whole-group discussion in which students discuss why, according to this article, lawyers engage in rituals during trial. During this discussion, resist the urge to answer the question yourself. Instead, push the conversation along by doing the following:

- Ask follow-up questions, including

- Requests for clarification.

- Requests for additional support for students’ ideas.

- Requests for further development of their ideas.

- Requests for explanations of how individual student’s ideas build on or relate to what students have said previously.

- Requests for students to summarize the ideas that are on the table.

- Draw students back to the text. Asking “What line?” questions and otherwise referring back to the text is critical if students are to grow accustomed to doing text-based work. Remember that apprenticing students into text-based work is as important as negotiating responses to the question in play.

- Be patient, but also be persistent in your quest for responses to the question.

- Ask students to talk to one another rather than to or through you. Sup- port students to extend, confirm, or critique each other’s ideas.

- Work to ensure that everyone has an opportunity to participate. Establish the expectation that everyone’s idea counts and that people get smarter by working together to explore difficult questions or ideas.

- Ask follow-up questions, including

- In addition to facilitating this conversation, work hard to capture and distill the major ideas that students are developing on the board or a chart. Push students to help you build text-based explanations to support them. This will ensure that students get a glimpse of what it looks like when someone builds a text-based explanation.

- As the discussion is winding down, ask students to take 5-7 minutes to reread their quick writes and make revisions based on the discussion they just engaged in. Explain that they might revise their quick write to do any of the following: change their response to the question, incorporate additional or different evidence from the text, or provide a more detailed explanation of the evidence. As students are revising their quick writes, circulate around the room to offer support and assistance as needed.

Title: The Reasons Weiser Begins and Ends His Article with Mr. Richman

Teacher Manual Instructions:

Session 1-D

- Convene the whole group and facilitate a discussion in which students discuss why they think Weiser begins and ends his article with Mr. Richman. During this discussion, resist the urge to answer the question yourself. Instead, push the conversation along by doing the following:

- Ask follow-up questions, including

- Requests for clarification.

- Requests for additional support for students’ ideas.

- Requests for further development of their ideas.

- Requests for explanations of how individual student’s ideas build on or relate to what students have said previously.

- Requests for students to summarize the ideas that are on the table.

- Draw students back to the text. Asking “What line?” questions and otherwise referring back to the text is critical if students are to grow accustomed to doing text-based work. Remember that apprenticing students into text-based work is as important as negotiating responses to the question in play.

- Be patient, but also be persistent in your quest for responses to the question.

- Ask students to talk to one another rather than to or through you. Sup- port students to extend, confirm, or critique each other’s ideas.

- Work to ensure that everyone has an opportunity to participate. Establish the expectation that everyone’s idea counts and that people get smarter by working together to explore difficult questions or ideas.

- Ask follow-up questions, including

- In addition to facilitating this conversation, work hard to capture and distill the major ideas that students are developing on the board or a chart. Push students to help you build text-based explanations to support them. This will ensure that students get a glimpse of what it looks like when someone builds a text-based explanation.

- As the discussion is winding down, ask students to take 5-7 minutes to reread their quick writes and make revisions based on the discussion they just engaged in. Explain that they might revise their quick write to do any of the following: change their response to the question, incorporate additional or different evidence from the text, or provide a more detailed explanation of the evidence. As students are revising their quick writes, circulate around the room to offer support and assistance as needed.

Title: How Superstitions Can Help and Hurt Us

Teacher Manual Instructions:

Session 2-B

- Place students in trios so they can share what they marked and explained related to how superstitions can be helpful and harmful. Then, ask the trios to discuss the following question:

- Why does Klosowski advise readers to embrace some superstitions cautiously and not to embrace others at all?

- Why does Klosowski advise readers to embrace some superstitions cautiously and not to embrace others at all?

- Facilitate a whole-group discussion of the same question. During this discussion, work with the class to generate a list of how superstitions can help and hurt us. Capture this on a chart titled “How Superstitions Can Help and Hurt Us.”

- As the discussion is winding down, tell students that Klosowski seems to understand that some people might find what he writes about embracing superstitions hard to swallow. Ask students to return to their trios and take a few minutes to skim through the article to determine how Klosowski acknowledges objections to what he writes. In other words, how does Klosowski address readers who are likely to disagree with him? What does he do to try to convince those readers of the validity of the information he provides? As students are working, circulate around the room to offer sup- port and assistance as needed.

Checks for Understanding

Title: “In a Field of Reason . . .”: Unfamiliar Terms and Confusing Moments

Teacher Manual Instructions:

Session 1-A

Reconvene the class and facilitate a whole-group share where the class collaborates to create the first two columns of a second master chart titled “‘In a Field of Reason . . .’: Unfamiliar Terms and Confusing Moments.”

To create this chart, call on students to share the unfamiliar terms and confusing moments from their group list. Capture these in column two of the class chart. Be sure to include page and line numbers for each term or moment in the first column.

Wrap up the work in this session by asking students to share the one or two things they learned from this text that they found most interesting or surprising.

Title: What We Learned About Identifying and Resolving Unfamiliar Terms or Difficult Moments

Teacher Manual Instructions:

Session 1-B

Finally, ask students to reflect on the search and study work with a discus- sion of the following two questions:

What more did you learn about this text from doing the search and study? Add relevant responses to the class version of the “What We Learned About Superstitions and Rituals” chart.

What did you learn about working through unfamiliar terms and confusing moments from doing the search and study work? What did you do to tackle some of the most challenging moments? Capture responses on a new chart titled “What We Learned About Identifying and Resolving Unfamiliar Terms or Difficult Moments.”

Session 2-A

Finally, have students turn to a partner and talk about what more they learned about the process of identifying unfamiliar terms or confusing moments. Ask a few students to share and add any new responses to the chart that was begun in the previous module titled “What We Learned About Identifying and Resolving Unfamiliar Terms or Difficult Moments.”

Session 2-B

Finally, ask students to reflect on the search and study work with a discussion of the following questions:

What more did you learn about this text from doing the search and study? Add relevant responses to the “What We Learned About What We Learned About Superstitions and Rituals” chart.

What did you learn about working through unfamiliar terms and confusing moments from doing the search and study work? What did you do to tackle some of the most challenging moments? Add relevant responses to the chart created in the previous module: “What We Learned About Identifying and Resolving Unfamiliar Terms or Difficult Moments.”

How can this information help you as you read texts in the future?

Title: “Embrace the Supernatural”: Unfamiliar Terms and Confusing Moments

Teacher Manual Instructions:

Session 2-A

Reconvene the class and facilitate a whole-group share where the class collaborates to create the first two columns of a new master chart titled “Embrace the Supernatural”: Unfamiliar Terms and Confusing Moments.

To create this chart, call on students to share the unfamiliar terms and confusing moments from their group list. Capture these in column two of the class chart. Be sure to include line numbers for each term or moment in the first column.

Finally, ask students what questions they have after reading this text. This is the time for students to share the general questions that came up as a result of reading this text (e.g., “Is it true that there’s no scientific evidence that Vitamin C prevents colds?”) as opposed to terms or moments that are un-familiar, confusing, or unclear. Add these questions to the “Our Questions About Superstitions and Rituals” chart created in Module 1.

Wrap up the work in this session by asking students to share the one or two things they learned from this text that they found most interesting or surprising.

Independent Reading

Title: Reading Log

Teacher Manual Instructions:

Independent Reading

As you transition to independent reading, discuss how students can keep a reading log. Show students how you would like them to set up and use their reading log to record their independent reading this year. An example of one way a reading log could be set up is provided nearby. You may choose to have students create a table in their notebooks, use a pre-made sheet, or a digital format.

Explain to students that they should make an entry in their log only after they have finished a book. You will need to negotiate with students how to handle the entry of magazine readings (for example, entire issues versus individual articles).

After students have set up the log, including proper headings, creating the grid, etc., show students how to make an entry.

Answer any questions students have about the reading log.

Begin independent reading.

Consider conducting individual reading conferences with students as they are engaged in independent reading. In No More Independent Reading Without Support, Debbie Miller and Barbara Moss (2013) suggest that during early conferences, you should listen to students and work to build trust: Ask students how they view reading and how they think of themselves as readers; ask what they are interested in. Over time you can ask more about what they are reading and about how you can help them or what they are struggling with. Use what you learn from these conversations to guide additional instruction with groups or with the class.

Title: Independent Reading – Individual Planning Sheet

Instructions:

Title: End of Marking Period Self-Assessment

Instructions:

Unit Resources

Title: Argument: Writing Across Texts Explaining the Behavior of Lawyers